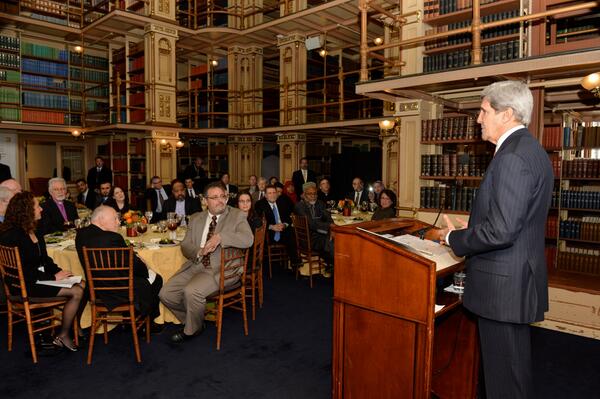

In October, Boca Raton Synagogue adopted a Civility Policy (since renamed Derech Eretz Policy) as an affirmation of our community’s commitment to debate, dialogue and disagree with respect and dignity, always focusing on issues and policies, rather than on people. Last week, I was reminded of the importance of this commitment when I traveled to Washington D.C. to participate in an interfaith lunch meeting with clergy from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Dr. John J. DeGioia, President of Georgetown University, invited us to meet with Secretary of State John Kerry to discuss the Israeli-Palestinian peace process and to dialogue among ourselves in an effort to build bridges and strengthen relationships.

Following three moving invocations, one from each faith, Secretary Kerry addressed us and shared his perspective on the peace process. He spoke passionately and enthusiastically as he articulated his argument for why success in the peace process is more important right now than ever and shared why he is so optimistic that the factors are in place to reach a final agreement that will secure a real and lasting peace. He referenced the concessions on both sides in the form of the Palestinians having held off from pursuing action at the United Nations and Israel having released over 100 prisoners.

In an op-ed in Ha’aretz following our meeting titled, “How John Kerry Won Me Over,” Rabbi Eric Yoffie, past president of the Union for Reform Judaism, expressed why he found the Secretary of State’s words so compelling that day and how, in his words, he “left the meeting convinced that chances for peace are better now than they have been in a very long time.”

Secretary Kerry laid out for us why he believes the status quo is not sustainable, and that what lies ahead for Israel if they cannot arrive at a peace deal is a “boycott campaign on steroids,” arguments he continued to advance in other venues in the days that followed. Abe Foxman of the ADL, who wasn’t present at the meeting, but was responding to similar sentiments expressed by Secretary Kerry elsewhere, was highly critical of Secretary Kerry’s invoking the threat of a growing boycott movement. In an open letter to Secretary Kerry, he wrote: “Describing the potential for expanded boycotts of Israel makes it more, not less, likely that the talks will not succeed; makes it more, not less, likely that Israel will be blamed if the talks fail; and more, not less, likely that boycotts will ensue.”

In Israel, rabbis identifying themselves as “The Committee to Save the Land and People of Israel,” in an open letter to Secretary Kerry, wrote this week: “Your incessant efforts to expropriate integral parts of our Holy Land and hand them over to Abbas’s terrorist gang amount to a declaration of war against the Creator and Ruler of the universe.” They compared Secretary Kerry to Haman, Nevuchadnetzar, and Titus and promised Heavenly retribution if he continues his efforts.

The RCA and OU were quick to disassociate themselves from these rabbis who claim to represent “hundreds of other Rabbis in Israel and around the world” by saying: “We, the leadership of the RCA and the OU, repudiate this letter and the rhetoric they have deployed. While the people of Israel and Jews around the world may properly possess serious concerns about proposals Secretary Kerry is putting forth, such concerns must only be expressed with civility and on the substance of the issues, not degenerating into personal venom and threats.”

Listening to Secretary Kerry last week, I heard a genuine and sincere man who sees the implications of his efforts extending far beyond the political and diplomatic spheres alone. He seemed to be speaking from his heart when he described a vision for bringing a peace that would position Israel as the center of the Middle East for commerce, innovation, trade, travel, and culture. I personally saw no reason to doubt his sincerity, question his motivation, or be skeptical of his ultimate goal.

That said, unlike Rabbi Yoffie, I was not won over by his argument about the prospects for peace right now, and I continue to have grave concerns for our beloved Israel and her citizens. Fortunately, I had the chance to voice them in the form of a question I posed to Secretary Kerry.

After thanking him for the opportunity to meet and for his efforts on behalf of peace, I asked, “Mr. Secretary, you say that the status quo is unsustainable and there is no choice but to come to a final status agreement. But before Oslo, we also heard that the status quo was unsustainable, while in retrospect, the status quo was far better than the thousands of Israeli lives lost post-Oslo. Before the Gaza withdrawal, we were told the status quo was unsustainable, but in retrospect, it would have been far better than the 40,000 rockets that subsequently rained down on Israel. Why will this time be different, and how can we be so optimistic and confident that we won’t,once again, end up longing for the status quo even if it was just the lesser of two evils?

“I wish I shared your optimism,” I continued, “but Israel has twice offered 95% of the territory asked for and twice their offer was rejected. Why, Mr. Secretary, are you so optimistic that this time will be different? And lastly, you equated not going to the UN with releasing over 100 prisoners, but they are not parallel concessions. Israel seems to consistently be asked to make concessions for peace that are irreversible and contain extraordinary risks and dangers. The Palestinians can always decide to go to the UN tomorrow, but land cannot simply be taken back. Prisoners, many of whom are in fact murderers, cannot just be called to report back to prison. Wounds, scars, and trauma suffered by those uprooted from their homes and by those tasked with uprooting them, don’t simply heal and disappear. Please, Mr. Secretary,” I concluded, “I truly want to be more optimistic; help me understand how or why.”

Remarking that he was so happy to be asked that question, Secretary Kerry proceeded to give a very thoughtful answer, one that made some very good arguments that I had not heard or considered before. Nevertheless, they didn’t fully satisfy or convince me.

But in truth, I am not the one who needs to be convinced or persuaded. It is Israel’s government and its people who will be forced to live with the consequences of this process and its conclusions. Their opinion and vote are what counts and what will ultimately shape the future for Israel. If we truly want our voice to matter on what concessions are made or how far this process goes, we should move to Israel and participate in the public referendum that has been promised before any final agreement is implemented.

Secretary Kerry had to leave the meeting soon after this exchange, but the experience was far from over. The interfaith dialogue was, in fact, just beginning as members of the clergy – Jewish, Muslim and Christian – stood up one by one and shared their thoughts, impressions, concerns, hopes, and aspirations. Everyone who spoke did so respectfully, with moderation, and with an apparent commitment to attaining peace and harmony, even if we disagreed on what “peace” means or how it is achieved.

I was struck and uplifted by the level of discourse shared by the diverse religious leadership gathered. We are all equally passionate about our positions and secure and confident in our analysis and understanding of the situation. We all entered the conversation unlikely to be persuaded or swayed to change our understanding of history, our people’s narratives or our prescription for what is necessary to bring peace for Israel and her neighbors. And yet, those differences did not have to create animosity, tension or personal attacks.

Though it likely wasn’t the primary goal, the interfaith lunch meeting accomplished something very significant. It set an example and model of our capacity to be honest, forthright and direct about our differences, in conversations at the highest level with the Secretary of State and with clergy of other faiths, all with civility, mutual respect and graciousness. Last week reminded me that we need not be defensive or apologetic for our positions. We must confidently speak truth to power when given the opportunity. But we must remain vigilant in maintaining dignity, even as we express our differences.

If every participating clergy member went home and preached about our experience as an example of civil discourse for our communities to emulate, the gathering was valuable and productive indeed.